This

trilogy of novels has been adapted into two TV series, the best known one is

American, however the story is set in the United Kingdom and so this review is

of the BBC production based on the novels. The books were written by Michael

Dobbs, a former Member of Parliament who has seen the political world from the

inside and so his insight holds some validity. The plot follows the political

career of Francis Urquhart MP who is the Conservative chief whip in the near

future, relative to the time of writing, just after the resignation of Margaret

Thatcher; this shows remarkable foresight on Dobbs’ part. It also reveals that

what becomes public in politics is often brewing in secret a long time

beforehand. Urquhart’s job as the chief whip is to try and maintain loyalty to

the party among the MP’s in government and this puts him in a position to know

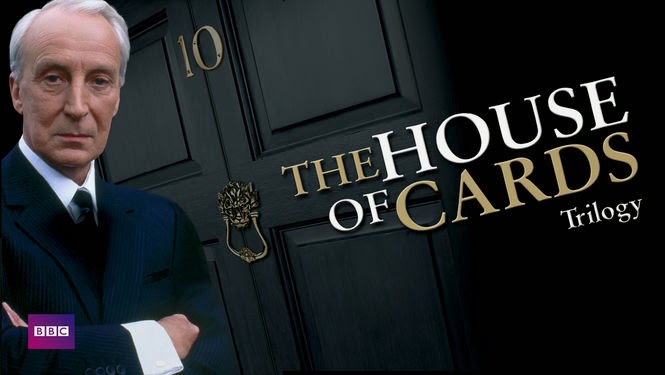

a lot of the secrets of his charges. Urquhart is brilliantly played by Ian

Richardson. He won a BAFTA for his performance and I think he is one of only two

actors who could play that character; the other being Christopher Lee. Urquhart

has ambitions to become Prime Minister and he uses the insider information he

has on his political rivals to blackmail and discredit them, and in doing so he

worms his way to power. At first these machinations are quite light-hearted; he

addresses the audience with monologues about his personal feelings. Later on

though it becomes clear that there is no level he won’t stoop to in his quest.

By the end of the first series he’s murdered two people. He poisons the party’s

press secretary and throws a young journalist off a roof garden. By the end of

the second series he kills two more people by planting bombs in their cars and

blaming the IRA, a satisfying reference to a false flag attack. He justifies it

to himself by saying it’s “necessary for the country”. It came as no surprise to

me when it revealed that his favourite book is The Prince by Niccolo Machiavelli. He is extremely clever, an evil genius,

and he can always tell intuitively when people are lying to him. Eventually he

achieves his goal and becomes Prime Minister and is nicknamed “F.U.” which is appropriate

because it sums up his attitude to the people. He finds an unexpected challenge

when a new king is crowned and the monarch is a kind and caring man who is openly

hostile to Urquhart’s government. As always, the PM digs up some dirt on the

king and turns it into a weapon to fight him. Several times the viewer is given

hope that F.U. is about to get his comeuppance, and again and again he thwarts

his enemies. It takes a long time before justice is done. One of the most

instrumental characters is Corder, Urquhart’s bodyguard, who pays an overtly

background role. Rather like Brutus in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, in the end is the crucial lynchpin in the downfall

of the emperor. There are some admirable people involved in the programme, like

the king, Urquhart’s secretary Clare Carlson, and Tom Makepeace who is sacked

as foreign secretary by F.U. and so works with Carlson and others to bring him

down.

After

watching the trilogy, you might wonder why there is anything of interest within

in from a HPANWO-esque perspective. The only conspiracies are ones feasible

from a mainstream standpoint, no hidden hand, no Freemasonic influence and no

sign of Illuminati control. The series shows a distinct lack of conspiratorial

awareness. This is not to say that the plot specifically precludes those

things, just that it appears oblivious to the possibility. Nevertheless I think

House of Cards and its sequels are revealing

about how dysfunctional and corrupt a government can become due to the moral decrepitude

of those involved. Urquhart himself is a merciless and deeply cunning

individual. He lies effortlessly and manipulates people as easily as he

breathes. His victims in the House are themselves almost as bad: selfish,

shady, weak, amoral, materialistic and foolish, culminating in the repugnant Geoffrey

Booza-Pitt, Urquhart’s most loyal minister. They prostitute their own wives, step

on their own allies for the promise of a knighthood and cower before Urquhart

the moment he threatens to take away their position. The image the story gives

us of the world inside politics is like Yes

Minister without the laughs, a dark and confusing maelstrom of degeneracy

and deceit. In such an environment any kind of conspiracy is possible.

The series is available on YouTube at

the time of writing:

House

of Cards episodes:

To

Play the King episodes:

The

Final Cut episodes:

2 comments:

Brilliant classic series. Thank you for posting! The grotesqueness and reality of what is 'politics' in all it's nakedness. The scene where a bomb goes off 'Its not one of ours prime minister'.

It really is revealing isn't it, X. Recommend it to your friends before the next election!

Post a Comment